“We might drive for hours like that, basically in a cigarette box.”

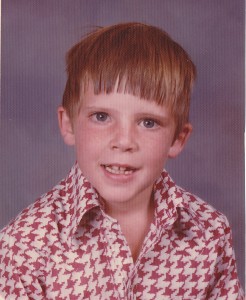

PATRICK

I grew up relatively poor. My dad had different jobs in different places—I was born in Seattle, we lived in Oregon for a while, lived in Colorado for a while. At some point we moved to Oklahoma where my father had grown up. He had lived in a dirt-floor cabin as a kid, so returning to that town in Oklahoma was ultimately for him a retreat to a place of comfort—not a financial comfort, but an emotional comfort.

My dad had always smoked for as long as I’d ever known him. He joined the army when he was seventeen or eighteen and I think because of some of the stress he’d had as a kid—he’d had a horrible family life—he started smoking and he never stopped. He smoked one to two packs a day for his entire adult life. I still remember: He liked Benson & Hedges Menthol 100s. He bought those things one carton after another. Frankly, cigarettes were at the top of his spending list.

In fact, in the little house that we lived in Oklahoma there was a smoke line in the curtains. Because he would smoke at the same rate it would fill the room of the house up to a certain level and just sit there. You could see it—after so many years it actually yellowed the curtains to a line three or four feet high.

He would also smoke in the car. I still remember he’d roll the driver’s side window down about a half an inch and then we’d all pretend that that would miraculously suck all of the cigarette molecules out of the car. We might drive for hours like that, basically in a cigarette box. So I was very accustomed to cigarettes and cigarette smoke as a kid.

For a long time the effects of smoking didn’t show much because he had a very physical job. But you know, as a kid you worry about your parents and I’d always kind of nagged him, off and on. I tried to explore whether he could quit smoking and he did what most smokers do, which is he made halfhearted attempts—but the truth was he wanted the cigarettes much more than he wanted to deal with what was driving him to want cigarettes so much.

As soon as my sister was out of the house he and my mother divorced almost immediately. He was living by himself; he was doing okay. He was independent, but as soon as he retired from that that physical job he put on a bunch of weight and I could tell that something was changing. He always had a bit of a hack, a bit of a cough, but it was different. His coughs were longer and I could hear that there was more fluid in them. I kept saying, “Maybe you should pull back,” and nagged him about stopping. But he was just in denial. He’d have thirteen excuses and I’d push him and question him and then he’d get frustrated and go have a cigarette.

I finally realized there was no talking to him about it. It was such a deeply ingrained part of his life and emotional functioning that he would never stop. And, at that point, it wasn’t worth stopping. It was a keystone that was holding a lot of things in place. And I finally accepted that. I gave up on saving him from cigarettes. I just accepted that whatever was going to happen was going to happen.

So one Christmas I did a lot of research and went and bought a really nice World War II-style Zippo silver flip-open lighter—the cool kind cowboys would use in movies—and had it engraved really nicely. After I gave him that lighter I never spoke to him about cigarettes again. I quit trying. We never had a direct conversation about it, but we stopped having negative and stressful exchanges about quitting cigarettes.

Well, he slowly got worse. Three or four years later, five years maybe—I can’t remember exactly—he was diagnosed with advanced lung cancer. Then 60 or 90 days later he had a massive stroke and passed away.

I always felt better for having quit on the whole subject of asking him to quit cigarettes. Because it just made me miserable and made him miserable. In many ways it was a big relief. I felt like I had done everything I could. And honestly, I don’t think he could make another decision. To yank those cigarettes out of his life would have been to pull the cornerstone out of a house. In hindsight I wonder what sort of other things would have happened to him emotionally had he tried to remove that.

The funny thing was I wanted him to use the lighter—to carry it around and keep it close to him, to think of me. But he loved it so much he wouldn’t use it! He just put it in a little frame and then put it on the fireplace mantle as a memento. I had filled it with lighter fuel for him and it worked great. He might have used it once or twice but generally he didn’t want to tarnish it or scratch it. So for him it was a legitimate keepsake.

In hindsight it’s one of the positive memories I have about my dad. He really appreciated that gift. I even saw him a year later, the first time I had noticed he had framed the lighter instead of using it, and I said, “Dad, why don’t you use this?” He still had a smile on his face. He just liked it so much and he didn’t want to get it scratched or tarnished. He wanted to show it off, this lighter of all things.

♦