“These people are like gazelles… whereas I was a rhinoceros or something.”

MAC

Athletically I was always kind of a plodder. I didn’t have a tremendous amount of natural ability, but I discovered in fifth grade that I was really good at a particular game of tag we would play at recess. It was sort of like a zombie war. If you were “it” each person you touched would then join your army and then they would continue helping you chase down other people. And I found out that I was a very good chaser of people because I could hunt down anybody—all I had to do was jog after them at a leisurely pace until they got tired. And I could tag them! Even the fastest kids in our school would wear out eventually. I thought, “I’m pretty good at this. This is my skill!”

I ran cross country throughout high school and I was always one of the top three runners on the team. But I was certainly no shining star or brilliant runner—even regionally I was just not that good. In races I would come in the top group but I would never win anything and I certainly didn’t advance to the state championships. I did, however, have this belief that distance running was a purely egalitarian endeavor and that anybody could become good at it if they just put in the time and energy and trained right. I thought it was fundamentally different from sprinting, for example, which I always viewed as a product of natural ability. People who got good at distance running were really impressive to me because it showed how much effort they had put in. I knew if only I worked hard enough I’d be able to get there too.

After graduation I went to Dartmouth College, which is not a big player on the national stage in any of the major sports. I thought since they were a small school that maybe I’d have a chance to go out for the cross country team and continue running, and that would be fun. Well, unbeknownst to me, Dartmouth was actually a NCAA Division 1 powerhouse in cross country at the time. They had come in second nationally two consecutive years, with no scholarship athletes, and they were ranked in the top ten when I arrived. I didn’t know any of this. The first week of school I stopped by the track and field office to see if it was possible to walk on the team as someone who hadn’t been recruited. I introduced myself to the assistant coach and he asked me what events I ran in high school and what some of the times were. I told him and he kind of smiled and asked me whether I wanted to try out for the women’s team. And I wasn’t offended by that; I was just sort of surprised. The fact was there were several members of the women’s team whose times were faster than what I had run in high school. Significantly faster.

So I showed up on the day that the head coach had designated and he had us do a six-mile warm-up run. Then he broke us up into four groups based on level of ability. He had most of the walk-ons in the slowest group, including me. He told us we would be doing one-mile interval repeats around the top of this golf course, on grass. We were to run the first mile in 5:20. I thought, “Ok, I can do that.” He said, “Go” and we ran and came through, in more or less that time. Then he told us to take four minutes jogging rest, and when the four minutes were about to expire, he said, “Okay, I want you to do another one, and this time I want you to kick it down to a 5:10 mile. Go!” And I was able to do that too. But it hurt! Then he gave us another four minutes of rest. Then I started to worry. I had never done an interval workout like this before, especially after doing a six-mile warm-up—with people who were all clearly faster than I was. The coach said, “Now I want this one to go just a hair under five minutes.” I kind of gulped, thinking, “I don’t know if I can do this, I don’t think I can do this.” And then, “Go!” And sure enough, I couldn’t! I was dropped by the group fairly early and I think I ended up coming through in about 5:45, way behind everybody else. The coach said, “All right, you’re done. You can go home.”

But he let me continue to train with them even though I wasn’t really a member of the team. I wasn’t traveling with them, I was just working out. Just to put it into context, there were about forty men who trained with the team at these workouts and I was pretty clearly the slowest. I never finished a workout for that whole season. But by the time we got to the end of the regular cross country season—late that fall—I was in better shape than I’d ever been in my life.

That summer I went back to L.A. and made the decision that I was really going to dedicate myself to training like I had never trained before—not only running very high mileage, but also going to the gym and lifting weights and doing other things as well. I was averaging 115 miles a week. Five days a week I would run twice a day and then I would do some sort of a speed or strength workout on Saturday and then on Sunday I would do a really long run. And when I got injured for portion of the summer, I ran in the swimming pool. I don’t even think I missed a day of training. I got faster and better, but I feel like I was just getting better at handling the pain and suffering that comes along with this sport.

I came back to school in the fall and everything was different. It was kind of amazing. I’ve never felt so validated or gratified because all of a sudden I was able to hold my own. I wasn’t one of the top runners on the team by a longshot but I was comfortably in the middle. Well, the lower middle. That season there was an invitational meet in Albany, New York, that a portion of our team went to. I was running out of my head that race. I was running stride for stride with these two guys who I had never been able to keep up with before, right into the last couple hundred meters of the race. And all of a sudden I just completely lost it. I went careening off the course into the crowd of people, fell down, and nearly passed out. Then I got back up and staggered over the finish line. It was an absolute mess. The level of pain that I had to undergo to stay with these people was really terrible. I just couldn’t make myself suffer through it again for such little return. But I was finally faster than all the women. And that year I got a varsity letter sweater that they award to people on the team, and I felt very proud of myself.

So that summer I trained just like the previous summer, but when I came back in the fall I wasn’t appreciably better than I had been the year before. I remember wondering, “What’s wrong with me? Why am I not faster than I was before?” I started to feel like I had hit my ceiling. I would see hotshot runners out of high school and they would be out of shape, not training at all, and I would be training year round. Then, two weeks into the season, once they started getting used to running again, they would be able to completely blow my doors off. These people are like gazelles, you know? Whereas I was a rhinoceros or something. And I feel our motivations were different. They were trying to win the race. I was just trying to show that I belonged.

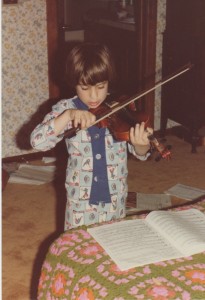

So I resigned from the team after the fall season junior year and decided instead to try out for the school symphony orchestra. And I went about it in the same way. I had played violin as a kid but hadn’t played it in years. I was so out of practice and wasn’t good, but I was intrigued by the idea and I knew I was going to be in L.A. for four months, and I decided that it was something I wanted to try and do. And I remember getting a teacher and going through this rigorous violin training program to try out for the orchestra in the spring.

♦