“I just wanted to win trophies.”

KAREN

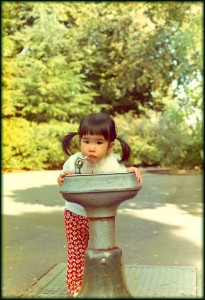

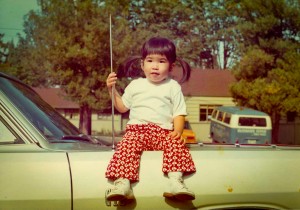

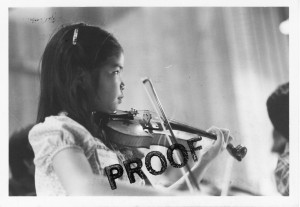

I started playing violin at the age of three. When I began preschool I saw a bunch of bigger kids playing the violin and I told my mom I wanted to do that. So I started in their little preschool program and at the age of four I had my first lessons with my first teacher, Miss Fugunaga, who pretty much taught me all the way up through high school. By the time I was six my mom had me practicing an hour a day and I won my first Bach competition. So I guess some people would say I had some talent in it. I was really competitive, actually. That was my thing: I just wanted to win trophies. Anyway, when you start at three years old, by the time you’re twelve you’ve played nine years. And then you can’t stop because you’re really good at it and your mom will say to you, “Are you really going to quit? Because you’ve been doing this for nine years!”

In my junior year of high school I was taking classes at the Colburn Music School and I had been practicing the Mozart Concerto in A Major for the year. I even took masters classes with some of the great teachers there just to really perfect this piece as best I could. I played in several competitions that year and won or placed in all of them. Probably the last one I did began as a regional competition in Orange County and I won that. After the regional you moved on to the Southern California competition and then to the state competition and then the nationals. One weekend I was getting ready for the Southern California competition and this kid Kevin came up to me. He had lost the L.A. County regional and was kind of a bad sport, so when I told him I had won the Orange County regional he said something to the effect of “Well, you only won because you’re in Orange County. L.A.’s much harder. Much tougher.” He told me about two Korean or Chinese sisters that competed against him and how really incredible they were. One of them had won and was moving on to face me in the Southern California competition. And somehow I learned who this girl was and how amazing she and her sister were and I really lost confidence. I can’t believe I did. Kevin was just talking trash, but somehow I wasn’t prepared for it. I believed him. I can’t believe I did. I got psyched out and I just quit practicing as aggressively as I usually do.

It was the first time I didn’t place in a competition. It was pretty heartbreaking. And devastating. It took me years to recover. I’m getting emotional about it now, so even now maybe I haven’t recovered from that. I was just thinking how I should really set myself free of it. When I look back on it I guess I didn’t want to lose and I was scared, so I practiced less and less. I practiced, but just not the way you need to practice, especially if you’re going to go up against somebody good. And it’s really too bad because I could have won. And even if I placed underneath the top girl I should have placed second. But I didn’t place at all. I just sort of lost it. I didn’t do anything wrong, I just didn’t play as well as I could have played. And the sad thing is that in that one competition and in that one loss, I lost the confidence—I lost the edge that I had since I was three years old. And that’s the edge that makes you really good. In that instant it was gone.

I quit practicing for that competition, but, sadly, I have yet to quit my perfectionism. It’s something I’ve struggled with all my life. I have to learn how to forgive myself for not being perfect all the time, which is not easy when you’re a perfectionist—I actually had to make a short film called Perfection as a way to get closure. As for violin, I think that a lot of this pressure came from within, because my mom and dad eventually told me that I shouldn’t be a musician because there’s no money in it. That after fourteen or fifteen years of training it wasn’t even worth anything. When you think about it, that’s kind of sad in itself: You start at age three and at seventeen they tell you all that you’ve done with your life isn’t worth anything. But that’s a different generation—that’s immigrants and their fear of artists and their fear of the unknown. For them music is good training—it disciplines you and you need extracurricular activities—but it’s not a stable career.

Years later I cut out an article by Steven Soderbergh, who apparently was a star pitcher in high school. He said that one day he woke up and just lost his competitive edge—and in that instant he was no longer a good pitcher anymore. Reading that, I felt comforted because I finally learned, “Okay sometimes you fail and you have to pick yourself up and keep moving forward.” But previously I didn’t know how to do that. I have always worried, “What happens if I lose my edge in filmmaking or something else?” But what I realize now that I didn’t know when I was young is that everybody is unique. Everybody’s story is different and everybody’s experience is different and everybody brings something different to the table. No matter what you do, nobody can replicate that. So sure, maybe I’m not going to be the best filmmaker in the world, but maybe I’m the only one who can tell these particular stories. And I can tell them the best of my ability. And that’s good. That’s great, actually.

♦