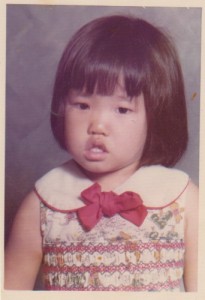

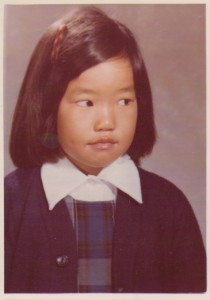

“I don’t think many people knew how unhappy I was.”

DIANA

Being from a family of Asian immigrants, I’ve never felt like I was part of the mainstream. No matter what generalizations are made about society, certain things just don’t apply to us because we are immigrant stock. I remember watching the Brady Bunch when I was a kid—I would watch how they did things, how they would have family meetings, how Mike and Carol, the husband and wife, would kiss and hug all the time. And the kids, whenever they would get up at night, they would put on a bathrobe and slippers. I particularly remember the bathrobe and slippers. Or they would wear shoes in the house. I used to watch it all the time and think, “Oh, that’s how Americans do things. That’s how it is! They have those family meetings, they talk about things, they’re always kissing.” It never occurred to me that nobody is like that. I just thought, “Oh, we’re different. Everything’s different.”

So it’s hard for me to tell a story about quitting, because I never felt like quitting was an option for me growing up. It wasn’t even a possibility. In my household, you stuck to it just because you started it. Both my parents had the same job for almost their entire careers; nearly thirty years at the same job. There was not this idea of just quitting or looking for something else. Once you had a good stable job you just kept it. Why quit? What’s your reason? If you say “I’m not good at it” or “I don’t enjoy it” and you quit, well, that seems a little indulgent. If it’s something you learn from you just kind of do it. Perhaps there’s a feeling of failure involved and maybe a little shame. I don’t know. I think we’re a long-suffering family in that regard.

I remember when I first got to law school and we were in orientation. They had new students come a week early and we had mock classes and we’d do all of these things where they’d introduce us to Philadelphia and the school. And when I was sitting there I thought, “This is not for me. I don’t enjoy this.” Class hadn’t even started and already I knew I didn’t belong there. But there was no option of quitting. I think my parents had already forked over about $10,000 in tuition. I was in Philly; I didn’t have a job to go to. I was already there moved into student housing. The idea of going home and saying I don’t like it was impossible. My parents would have to tell people, “She quit.” I would have to tell people.

But there were a number of people that quit law school after the first semester, after the first year, and I remember being surprised. I was stunned that someone could do that. It just didn’t seem possible. And I’m pretty sure those people weren’t kicked out for academic reasons; they just said it wasn’t for them. I thought, “Wow.” I mean, I’m sure they were just like me, with no job lined up, and here they were saying, “I don’t want to do this anymore. I’m going to do something else.” There was a sense of awe and a little bit of admiration that they could do that.

But also none of them were Asian. I’ve always felt like when non-Asian people hear that my parents paid for my education, a lot of times they’ll say things like “You’re so lucky,” but I tell people that that money comes with all kinds of strings attached to it. It doesn’t come for free. They pay for my education and with that comes a lot of the guilt—the feeling that I can’t quit. What embarrassment it would cause not just me, but my family. And the sacrifice that came with them forking over all of that money for me to go to that private school. Those folks who are paying for their own education, they probably have a ton of loans—they’re just going to deal with it on their own and figure it out. My bank was my parents and I had an obligation to them not to quit.

I hated my first few years of practicing law. I was really unhappy. But I would never admit that because once you say it out loud it’s true. You have to face it. I don’t think many people knew how unhappy I was. But I just plugged along and did it and now in retrospect I look back and I realize how stressed out and unhappy I was. But it’s part of what I said earlier about being long suffering. This is the hand you’re dealt; you just deal with it. You make the best of it. And you’ll be fine.

For many years after I graduated from law school I wished that I had quit early on. But now, twenty years later, it didn’t end up bad. I have a good steady job that pays me decently and I have financial security as a result of it. So in a sense I’m glad I didn’t quit. I stuck through it and now it’s not so bad. It’s okay. Whether I stayed or I left, my life is fine now.

If I had done something else, I might have wondered what would have happened had I stayed. If I had left, what would my life have been like? I think it would have been harder. I probably wouldn’t have the security I have now—the job security, the financial security. I don’t think I would have had it if I had taken another career path. Who knows? I don’t know.

♦